Something weird used to happen to me every time I visited my parents. I should probably start off by saying that visiting them wasn’t easy: it took at least a full day of plane travel to get to their house and I’d be a complete and utter wreck by the time we arrived.

For us, there was no popping by for dinner or a little impromptu babysitting. Visits were planned months in advance and included hauling a toddler, and all her stuff, through numerous airports and crowds of grumpy, pushy, smelly people. By the time I stumbled across my parents’ threshold, I’d be covered in juice and sweat, and mind-weary from chanting the phrase “never again” over and over in my head. And let me just say this: if there is a flight attendant out there who thinks s/he can get a child to sit buckled in a seat for five straight hours, I’ll give them my life’s savings.

But that chaos is normal for anyone who’s traveled with a toddler. The weird thing about visiting my parents is that I’d walk in their door and lose 25 years of my life. Oh, it didn’t always happen instantaneously; sometimes it took a day or two. But inevitably, at some point during my stay, the years would vanish.

It usually happened following a minor incident: someone would forget to pick up an item at the store, or a blanket would be left unfolded on the couch, or one of us would be two minutes late to the dinner table. Then mom would yell, my sister and I would say something snarky, and my dad would ignore us all. And just like that we’d fallen right back into the family dynamic that existed when we all lived together.

Never mind that I’m a university graduate and a wife and a mother; never mind that I’ve lived away from my parents longer than I lived with them; never mind that my sister and I get along just fine in every other location, thank you very much.

Here’s the thing about mother-daughter relationships: they’re complicated. We’re never too old to be our mother’s daughter, and our daughter never outgrows being our baby. It doesn’t matter what persona we show to the world, when we’re at home with mom we’re vulnerable to the role we’ve always played.

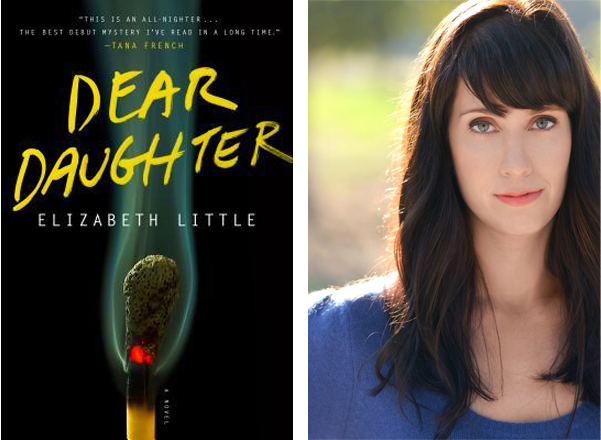

For Jane Jenkins, in Elizabeth Little’s novel Dear Daughter, that role includes being pretty, acting appropriately and keeping her mouth shut. Such is the life for a teenage daughter of the elite socialite and philanthropist Marion Elsinger. But Jane is a rebel who is beyond pretentious, and worse, she’s bored.

There’s one sure way of getting rid of all those ridiculous expectations, and a shotgun will do the job nicely.

Well that’s the theory Jane’s friends, the media, the jury, the judge, and the majority of the Western world all believe anyway. Jane herself wouldn’t be surprised to find out that she actually killed her own mother, but the problem is that she just can’t remember doing it.

Dear Daughter begins with Jane’s release from prison ten years after her mother’s murder. No one thinks she’s innocent and Jane’s freedom is loosely based on a technicality.

In disguise (and yet holding true to an obnoxious, entitled, teenage mentality), Jane follows the one lead she has that will prove whether or not she’s a killer. What she finds out? She most definitely, very certainly isn’t the only one who hated her mother passionately.

Dear Daughter is a page-turning, who-done-it thriller, perfect for the hectic pace of the holiday season. Read it for pure enjoyment, and be very, very thankful that your mother isn’t Marion Elsinger and your daughter isn’t Janie Jenkins. A complicated mother-daughter relationship, indeed.

Dear Daughter is Elizabeth Little’s debut novel. Viking, 2014.

Leave a Reply