Some books wash over you like a wave; they’re read quite easily, bathe you as you’re enjoying them and then recede, seldom to be remembered. Other books pull you down like a rip current; demanding your full attention and observation, leaving you almost breathless at the end. Those are the books you want to talk about, press into others’ hands and think about for days or weeks after closing them for the final time.

Some books wash over you like a wave; they’re read quite easily, bathe you as you’re enjoying them and then recede, seldom to be remembered. Other books pull you down like a rip current; demanding your full attention and observation, leaving you almost breathless at the end. Those are the books you want to talk about, press into others’ hands and think about for days or weeks after closing them for the final time.

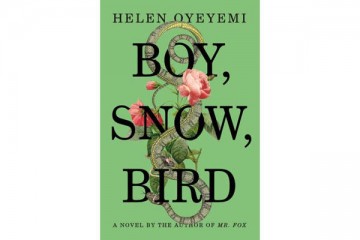

“Boy, Snow, Bird” by Helen Oyeyemi falls into that rip current category.

In the winter of 1953, Boy Novak arrives by chance in a small town in Massachusetts, looking, she believes, for beauty—the opposite of the life she’s left behind in New York. She marries a local widower and becomes stepmother to his winsome daughter, Snow Whitman.

A wicked stepmother is a creature Boy never imagined she’d become, but elements of the familiar tale of aesthetic obsession begin to play themselves out when the birth of Boy’s daughter, Bird, who is dark-skinned, exposes the Whitmans as light-skinned African Americans passing for white. Among them, Boy, Snow, and Bird confront the tyranny of the mirror to ask how much power surfaces really hold.

There is an awful lot to this novel; the themes are big, the characters complex and elaborate, and the writing is powerful, imaginative and inventive.

“Boy, Snow, Bird” wrestles with the theme of identity and selfhood; who we are and how others’ perceptions of us change our selves. Do our looks define us? Our race? Our gender? Read this novel and prepare to second guess your own ideas about beliefs and judgements.

Mirrors play a very big role in this novel, and readers are forced to contemplate the difference between what others see when they look at Boy. The novel opens with the line, “Nobody ever warned me about mirrors, so for many years I was fond of them, and believed them to be trustworthy.” For the rest of the novel characters survey the reliability of mirrors and grapple with their trustworthiness .

The characters are like matryoshka, the Russian nesting dolls. We are introduced to Boy and just as we feel we have a handle on her, a layer is peeled back, a relationship exposed or a plot twist revealed and out pops another version. Similar complexities arise as we get to know her stepdaughter Snow and her daughter Bird. All three deal with the dichotomy between how they see themselves, and how others see them (or want to see them).

Character is at the heart of the novel. Early, Boy says “As for character, mine developed without haste or fuss. I didn’t interfere – it was all there in the mirrors.” And later, “Where does character come into it? Just this: I’ve always been pretty sure I could kill someone if I had to…I wouldn’t kill for hatred’s sake; I’d only do it to solve a problem.”

Read “Boy, Snow, Bird”, and then press it into someone’s hand. This is not an easy read, but Helen Oyeyemi is an imaginative and lyrical writer we’ll be talking about for a very long time, and this novel is original and powerful.

Leave a Reply