Last year, while getting my eyes examined, I mentioned to my (very young) optometrist that I felt like the world was getting darker. I was having difficulty seeing things and was finding that I needed more light, especially while reading. I wasn’t going blind, he assured me. Apparently, a darkening world is a common complaint of women “who have reached my age.”

Well.

After the sting wore off a bit, I began wondering how it was possible that I had “reached my age” (while silently cursing my optometrist for so casually stating it). In my head, I’m perpetually about 32. Age is funny that way. I’ve chatted about it with my girlfriends and we all agree that the ages in our heads don’t match the reflections in our mirrors. Even my dad says he’s shocked by the old guy who stares back at him. How is it that time slips by so quickly?

There are days when I’m still surprised that there is a kid who calls me mom. And she’s twelve. I so clearly remember when my parents were my age and I was the preteen. How is it possible that I’m now the parent when so much of who’s inside of me still feels like that little girl? I suppose that it all comes down to the fact that we never, no matter how old we get, stop being our parents’ child.

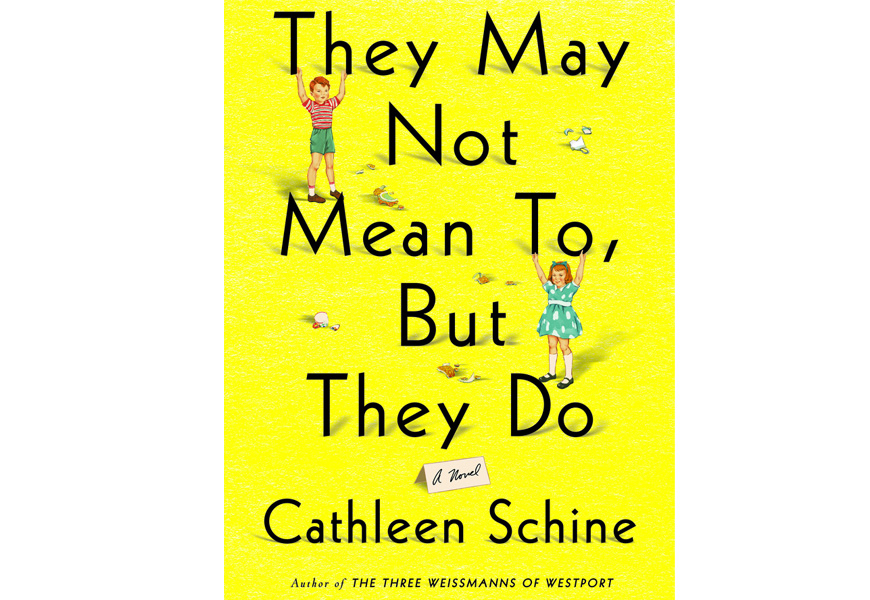

Molly and Daniel, in They May Not Mean To, But They Do, although grown with their own children, can’t stop worrying about their parents. Aaron and Joy are in their eighties and both suffer from declining health. They insist on caring for each other, however, and adamantly refuse to get outside help (no matter how many times their children suggest it). Daniel and Molly visit as often as possible but convincing their parents to hire a nurse, or move into assisted living, is a moot point.

Joy is proud of her independence. She may be eighty-six, but that doesn’t keep her from holding down her job at the museum and single-handedly caring for Aaron (whose dementia is getting worse). As much as she loves her children, their constant badgering of her to get help is wearing on her nerves. Don’t they recognize that it is her job, and her job only, to care for the man she loves?

But everything changes when Joy has a stroke. No longer able to care for Aaron, Joy must allow others to take over her daily duties. And when Aaron dies, Joy discovers that grief and loneliness are much harder symptoms to recover from than those of her illness.

They May Not Mean To, But They Do is a touching look into a close-knit family whose only fault is the level of concern they have for one another. Desperate to keep everyone happy and content, their (often hilarious) antics drive each other batty. Joy just wants to be left alone in her loneliness—apparently that is too much to ask.

Cathleen Schine is the author of The Three Weissmanns of Westport, The Love Letter, and The New Yorkers, among other novels. She lives in Los Angeles. Sarah Crichton Books, 2016.

Leave a Reply