Award-winning author Clare B. Dunkle was high on life. She lived overseas in beautiful Germany, her career as a children’s book novelist was taking off and, most importantly, her daughters were happy, healthy and teeming with exuberance. But almost without warning, Clare’s life crumpled when not one, but both daughters became ill. Clare’s eldest daughter had just overcome a severe bout of depression when the other was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. Her new memoir, Hope and Other Luxuries, recounts her five-year journey through her daughter Elena’s battle.

Award-winning author Clare B. Dunkle was high on life. She lived overseas in beautiful Germany, her career as a children’s book novelist was taking off and, most importantly, her daughters were happy, healthy and teeming with exuberance. But almost without warning, Clare’s life crumpled when not one, but both daughters became ill. Clare’s eldest daughter had just overcome a severe bout of depression when the other was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. Her new memoir, Hope and Other Luxuries, recounts her five-year journey through her daughter Elena’s battle.

In her memoir, Clare writes openly and honestly about her own struggle to remain patient and supportive to a daughter bent on destroying herself. Here she discusses with me her reasons for sharing her painful story and her advice for other moms.

CS: In Hope, Elena’s treatment of you is often hateful and accusatory, yet she remains loving towards her father. Speaking from my own experience, my daughter treats me differently than she treats her father even though she lives with both of us and we enforce the same rules. Do you think that Elena considers you her “safe” parent? Are we, as mothers, more easily manipulated and/or abused by our children simply because of our relationship with them?

CBD: I do think that our children are more ready to signal to us mothers that they’re unhappy or disturbed about something. At least, I know mine do. Back when they were younger, these signals often came in the form of complaints, crying, impatience or acting out. Why is that? Maybe it’s as simple as the fact that we mothers are more likely to say, “You’re not yourself today. What’s wrong?” Whereas a father might be more likely to punish based on the behavior and not look for the underlying cause.

This isn’t universal, though. I have a dear friend whose father was the one she took her troubles to. So that “safe” parent isn’t always the mom.

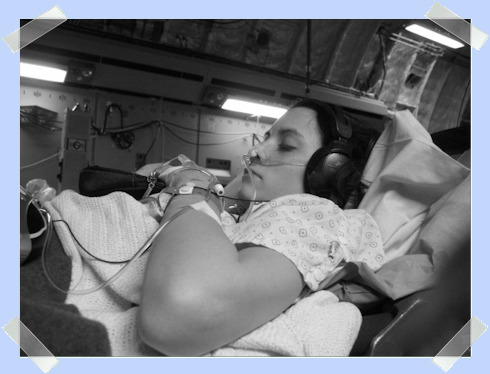

CS: You dedicated five years of your life to escorting Elena from hospital to hospital, clinic to clinic, appointment to appointment. Despite it all, she was so ill that she seemed determined to die. After supporting Elena through the ups and downs of her illness, you and your husband made the difficult decision to hold Elena to a contractual agreement. Although hostile and resistant, Elena agreed and began recovering. In hindsight, do you feel that you coddled or supported her too much during those prior years?

CBD: Honestly, no. Anorexia nervosa is a tremendously hard illness to overcome; one study suggests that it has a relapse rate of over 75 percent. During several of those prior years, Elena had been able to manage her illness while still living a full and productive life; she had made excellent grades and successfully worked several jobs. And earlier in the year of the contract, more gentle treatment on our part had helped Elena reach the difficult decision to seek help. She had already worked on her recovery in treatment centers for five months before we reached the point at which the contract became necessary.

I think that there’s a natural desire on all of our parts when dealing with such a dangerous illness to look for that perfect solution, the one that would have solved all our problems more rapidly and given us a shortcut. And contracts certainly have their place. But remember, the victims of anorexia are often victims of trauma as well. Taking away all of a trauma victim’s choices can simply echo that trauma and push him or her deeper into the disorder, or to suicide. The very first psychiatrist Elena had was determined not to coddle or support her: he was very harsh and even yelled at her. That backfired horribly: Elena became entrenched in her anorexia as a result of his behavior and wore it like a badge of honor. So I don’t think a contract would have worked earlier. It only worked because we all were at the end of our rope—Elena included.

CS: Hope and Other Luxuries was co-published with Elena Vanishing, a Young Adult memoir of the same time period written from Elena’s perspective. You mention in Hope that helping Elena write her memoir was a painful process. Was writing Hope painful for you as well, or did you find the experience cathartic?

CBD: It was a brutal book to write. I wanted to be fair to the other people in the story, and to the reader, too; I wanted the reader to be free to make up his or her own mind, to question my choices, and to be able to say, “I think she’s making the wrong decision here.” But that meant building uncertainty into every single scene and that meant leaving myself open to feel that uncertainty all over again. I spent a lot of the writing process agonizing over what I could have done differently.

CS: I found it very disturbing that you were treated so poorly by people in the medical profession. I can’t help but think that had you had two children with cancer, or a similar terminal disease, you would have been shown sympathy and support. Do you feel that your treatment was a result of the stigma associated with mental illness?

CBD: It’s true that some of the medical professionals treated both Elena and me poorly, but I have to say, others were wonderful. Still, I do think you’re right. Even medical professionals can misunderstand psychological illness and blame the patient or the family, as that one nurse did who told Elena she didn’t deserve medical treatment for her anorexia.

But it was some of the psychological professionals who treated me the worst and this I found the most disturbing of all. Those professionals who treated me badly were following a theory that it is the mother who causes her daughter’s anorexia. Of course, they didn’t explain that they believed that. In fact, they explained almost nothing to me. It was very cruel treatment all the way around. They were busy telling Elena and her adolescent peers in treatment—ALL of them!—that their families had caused their disease. Meanwhile, they were keeping us parents in the dark about our children’s dangerous behaviors. For instance, they hid from me the fact that my daughter was purging at the time. And purging can result in death.

The saddest thing about this particular chapter in Elena’s treatment history is that this psychological theory about mothers or families causing anorexia had been discredited a decade before. I recently spoke to the director of the Johns Hopkins Eating Disorders Program, and she said, “We knew in the nineties that that wasn’t true.” But in 2006, at one of the most respected treatment centers in the country, we were still facing this outmoded treatment. And I’m sure that there are still psychological professionals who are treating anorexics today based on this discredited and very cruel theory.

CS: What impact do you want Hope and Other Luxuries to have on its readers? What is your hope for the memoir?

CBD: I suppose I want Hope to reach the mother I was back when I thought my own family was invincible. Because my girls were so confident, happy and smart, I wasn’t worried about adolescence; I assumed that girls who had trouble with behavioral disorders then were girls who came from dysfunctional families. I was dead wrong. Modern life is so stressful and unpredictable that any mother may find herself facing issues such as adolescent anorexia nervosa. This isn’t just “somebody else’s problem.” It’s a problem any of us may face.

But I also wrote my memoir for the parents who are facing anorexia and its terrible consequences. I felt so alone when Elena was going through her worst days that I’d like to be there for those parents who are facing these things now. It isn’t that I have any answers. There’s no magic bullet—at least, not one that I’ve found. I just want to provide those parents a little company.

CS: What advice can you give to mothers of daughters, especially those of us who have tweens and teens? What should we be watching out for? How can we best support/model a positive body image?

CBD: I don’t know how much advice I can give; Lord knows my own methods were far from perfect. The most important thing I can say, I think, is to respect your children and remember how hard the teenage years can be. The upper grades of school can be harder than the hardest job.

It’s very important to make yourself a willing audience for your teens. Even though my daughters struggled and even though our relationship wasn’t necessarily the best, both girls came to me constantly to download: I knew all kinds of things about their friends and classes and favorite teachers and social activities. We moms are busy, so it can be tempting at times to shut this information down because so much of it is trivial, or to try to use it to steer things our way. It’s hard simply to listen and be interested and not to try to take control through that information, but teens want as much of the control as they can get and they’ll stop telling things if the information ends up getting used against them.

In terms of what to watch out for, I would say that it’s important to see your teenagers eat and to be aware about their relationship with food. Don’t let them just take breakfast with them. Make sure there’s time at home for meals. And if you see a sudden shift in happiness or behavior, get help!

Don’t do what I did and stop with the very first psychiatrist if what you hear doesn’t match what you think is true. Our first psychiatrist told us Elena was fine. She wasn’t fine. Elena was hiding the secret of her brutal rape from him and from us. I knew in my heart that she wasn’t fine, but I let myself believe the expert.

It’s true that modeling a positive body image can help, but we mothers only have so much influence over our children and our healthy attitude can’t help overcome genetics and trauma to prevent an eating disorder. I had never gone on diets myself and had a healthy attitude toward my own appearance. I had done my best to shelter my girls from unhealthy media messages and what I considered to be exploitative toys—I bought them healthy-sized fashion dolls, for instance, and wouldn’t allow Barbies in the house. Those techniques might have worked if Elena hadn’t gotten raped at thirteen. Up to that point, I had never seen her diet. But that rape, coming before her sexual identity had had time to form, just shattered her and destroyed her relationship with her own body. So be aware that you, as a mother, can do everything you can think of to nurture your child, only to see him or her destroyed by outside influences.

CS: How did Elena respond to Hope and Other Luxuries and your version of the events? What is your relationship like now?

CBD: Elena and I worked at every step of the way on her own memoir, Elena Vanishing; we read the drafts and revisions together and worked together to create every line. But when it came to Hope, Elena didn’t read it for a very long time. She couldn’t face it, and I didn’t pressure her to. She feels deep shame and regret over much of what went on during those years. She finally read it late last year and thought it was fair and I didn’t push her for more feedback than that.

Our relationship now is very strong. Indeed, it’s been strong for years. Elena and Valerie call me every day to chat. I realize what a privilege it is to have them share so much of themselves like that, and I try to be careful not to abuse it. My role nowadays is to be their loudest cheerleader, not to run their lives.

For specific information on eating disorders, please visit the websites run by the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) and the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD).

To read my review of Hope and Other Luxuries, click here

To read my review of Elena Vanishing, visit Great Read 4 Teens.

[…] A Mother's Life With A Daughter's Anorexia: An Interview With Author Clare B. Dunkle By Christine S… […]